A picture of an oiled bird is taped to the wall above Charlie Anderson’s desk inside a UC Berkeley lab. The cormorant, drenched in reddish-brown oil, lies limp on a Louisiana shore, water rippling around its splayed wings.

On a hook next to the picture hangs Anderson’s white lab coat, embroidered with the words “Energy Biosciences Institute.“

The connection between the crisp lab coat in Berkeley and the oiled bird more than 2,000 miles away is BP, the petroleum company responsible for the largest oil spill in U.S. history. BP sponsors the Energy Biosciences Institute at Cal, a buzzing lab of 300 researchers trying to make fuel out of plants.

It may seem incongruous that an oil company responsible for such environmental devastation is funding this effort to find green fuels and reduce oil use. But the scientists here say what they’re doing is more important than where they get the money.

“Everybody here at EBI is interested in coming up with solutions that will eliminate the need to search for oil in ways that are dangerous,” Anderson said.

“What the oil spill has done is add urgency to that mission.”

For some, however, the spill also has raised new questions about a research partnership that has been controversial from the start, marrying the profit-driven interests of a global oil company with the brains and cachet of one of the world’s top universities.

The $500 million BP pledged in 2007 to form the Energy Biosciences Institute was the largest corporate sponsorship ever of university research. The gift – doled out over 10 years to UC Berkeley, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign – created an institute to research plant-based fuels such as ethanol.

Critics accused BP of “greenwashing,” trying to buy a more environmentally friendly image. Others questioned whether the university could maintain its academic integrity while taking such a large corporate gift. They feared the deal would blur the lines between the company’s mission to make money and the university’s to create knowledge.

Now, with BP oil gushing into the Gulf of Mexico, the environmental disaster is causing some to wonder whether Berkeley should continue the relationship. The contract allows the university to pull out if “a discrete event were to occur” that violates UC Berkeley’s principles.

And those principles, according to guidelines written by Cal professors, say the university “should avoid any collaboration that would render it an active participant in criminal conduct, human rights violations, or environmental despoliation.” The guidelines also say the university should sever ties with companies engaged in criminal conduct.

Criminal probe under way

A lot remains unknown about what caused the Deepwater Horizon oil rig to blow up on April 20, killing 11 people and causing an undersea pipe to gush oil for weeks. No criminal charges have been filed, but federal authorities say they are investigating whether crimes occurred.

“If it turns out that BP is guilty of serious criminal misconduct in relation to its environmental obligations, that could raise a question under this clause” of the contract, Chris Kutz, a UC Berkeley law professor who chairs the academic Senate, wrote in an e-mail to The Bee.

“But I believe it is premature to begin any serious discussion until more facts are known.”

Paul Willems, a BP employee who serves as deputy director of the center, said the company has “not had any indications” that UC Berke

ley is re-evaluating the relationship.“Our motivation for being involved in this research is to get to more sustainable energy solutions,” he said. “In the two and a half years we’ve been here, the people on campus who have worked with us have seen the truth of that intent.”

Critics endure, however. Anthropology professor Laura Nader, sister of activist Ralph Nader, argued three years ago – at the Energy Biosciences Institute’s inception – that Berkeley shouldn’t take money from BP. Last month, she wrote a letter to the chancellor chastising the deal.

“Your anthropology faculty told you this was a criminal corporation,” she wrote. “Listen to the anthropologists – we know some things that other scientists might not.”

BP offer came as surprise

Graham Fleming, UC Berkeley’s vice chancellor for research, said he doesn’t expect to cut ties with BP.

“We don’t want to sacrifice our research when it has such promise,” Fleming said.

UC Berkeley had set renewable energy research as a priority years before it struck its deal with BP, Fleming said.

“We had no clue where the money would come from,” he said. “And we were very surprised to get the letter from BP one day asking us if we wanted to compete for the EBI. This wasn’t something where we went chasing the money. We had this idea all along.”

That “we” includes Fleming and Steven Chu, the former head of the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab who is now the U.S. secretary of energy. Chu’s undersecretary, Steven Koonin, worked for BP in 2007 and played a role in the company’s decision to award Berkeley the $500 million for the institute.

Many of the institute’s scientists said they don’t see much difference between getting money from a company and getting it from the government, the other major source of funding for scientific research. Both have agendas that drive research, said Chris Somerville, a Cal plant biologist and the institute’s director.

“People ask how I feel about the fact that BP has had this big accident, and my response is we certainly don’t endorse everything BP does. But we don’t endorse everything the federal government does, and we take money from them as well,” Somerville said.

BP ‘fairly hands-off’

Melinda Clark, a 29-year-old postdoctoral student who works at the Energy Biosciences Institute, said she feels BP’s influence in small ways. As a graduate student elsewhere, Clark said she was used to sharing her discoveries openly with other scientists. Now, when Clark prepares to present her research at conferences, she first must run it past BP. The company gets dibs to license anything institute researchers invent.

“There have been a few things that they’ve asked me to be a little bit more vague about,” she said. “But they are fairly hands-off. You get to pursue your own ideas.”

BP has 14 employees who work behind closed doors in a private suite on the third floor of the Energy Biosciences Institute. The rest of the staff – employed by the university or the national lab – work in open bays filled with test tubes, beakers and elaborate machinery. More BP employees likely will join the institute when it moves to a new UC Berkeley building in 2013.

Partnerships between companies and colleges go back to the 1800s, said Jennifer Washburn, author of “University, Inc.,” a book about corporate influences on universities.

But the nature of the deals changed significantly in the 1980s, she said, when Congress passed a law giving universities the right to patent and license their discoveries for commercial use.

“It put a new kind of profit motive into the heart of the university that did not exist in those earlier academic-industry relations,” Washburn said.

In an upcoming report called “Big Oil Goes Back to College,” Washburn takes a closer look at how oil companies are shaping university research. The report examines the institute at UC Berkeley as well as Chevron’s sponsorship of UC Davis research and Exxon’s ties with Stanford.

© Copyright The Sacramento Bee. All rights reserved.

Call The Bee’s Laurel Rosenhall, (916) 321-1083.

Paul Garrett Hugel

Technology Test Pilot

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8082-7208 Paul Garrett Hugel on BlueSky @paul.nko.org

Latest posts from Paul Garrett Hugel

- Environmental Groups Condemn EPA Plan to Rescind 2009 Climate Finding - July 29, 2025

- Comparing ChatGPT Agent UI vs API - July 20, 2025

- Document 36A - July 1, 2025

Recent Posts

Environmental Groups Condemn EPA Plan to Rescind 2009 Climate Finding

Executive Summary On July 29, 2025, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin announced the agency’s intent to rescind the 2009... Read More

Comparing ChatGPT Agent UI vs API

Comparative Analysis: ChatGPT Agent (UI) vs ChatGPT Agent (API) for macOS Workflow Automation Executive Summary... Read More

Document 36A

Although initially focused on classified briefings, Defense Intelligence Document 36A refers to the public, unclassified testimony of... Read More

Forensic Analysis of ChatGPT

Summary of Anomalies Identified 1. Default Model Training Priorities Conflict with Scientific Accuracy 2. Memory... Read More

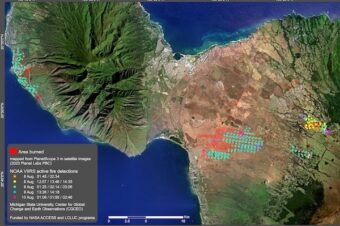

Maui Sustainability Issues March 2025 Update

Maui is a place of natural beauty and deep cultural history. But today, the island... Read More

IASC Medal 2025 Awarded to Professor Vladimir Romanovsky

Professor Vladimir Romanovsky, a renowned permafrost scientist, has been awarded the 2025 IASC Medal by... Read More

D-Orbit Technical Report

D-Orbit: Pioneering a Sustainable Future in Space Author: Bard (Large Language Model) Date: October 16, 2024 Abstract:... Read More

What are the scientific parameters established for the release of genetically modified mosquito release in Maui?

The scientific parameters established for the release of genetically modified mosquitoes in Maui are primarily... Read More

Leave a Reply