From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to:navigation, search

This article may contain material not appropriate for an encyclopedia. Please discuss this issue on the talk page. (June 2010)

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (June 2010) Corexit is a product line of solvents produced by Nalco Holding Company.

Contents

[hide]

[edit] Use

One variant was used in the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska. In 2010, Corexit EC9500A and Corexit EC9527A were used in unprecedentedly large quantities in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.[1] On May 19, 2010 the Environmental Protection Agency gave BP 24 hours to choose less toxic alternatives to Corexit, selected from the list of EPA-approved dispersants on the National Contingency Plan Product Schedule[2], and begin applying them within 72 hours of EPA approval of their choices.[3] BP has used Corexit 9500A and Corexit 9527A thus far, applying 800,000 US gallons (3,000,000 l) total[4], including the company’s estimate of 55,000 US gallons (210,000 l) underwater.[5]

[edit] Composition

The proprietary composition is not public, but the manufacturer’s own safety data sheet on Corexit EC9527A says the main components are 2-butoxyethanol and a proprietary organic sulfonic acid salt with a small concentration of propylene glycol.[6][7] Corexit EC9500A is mainly comprised of hydrotreated light petroleum distillates, propylene glycol and a proprietary organic sulfonic acid salt.[8] Propylene glycol is a chemical commonly used as a solvent or moisturizer in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. An organic sulfonic acid salt is a synthetic chemical detergent, such as dodecyl benzene sulfonate used in laundry detergents, that acts as a surfactant to emulsify oil and allow its dispersion into water.

[edit] Effectiveness

The oil film will be dispersed in small droplets which intermix with the seawater. The oil is then not only distributed in two dimensions but is dispersed in three.

Corexit EC9500A (formerly called Corexit 9500) was 54.7% effective in handling Louisiana crude, while Corexit EC9527A was 63.4% effective in handling the same oil.[9][10]

[edit] Toxicity and alternatives

The safety data sheet states “The potential human hazard is: High.”

According to the Alaska Community Action on Toxics, the use of Corexit during the Exxon Valdez oil spill caused “respiratory, nervous system, liver, kidney and blood disorders” in people.[

7] According to the EPA, Corexit is more toxic than dispersants made by several competitors and less effective in handling southern Louisiana crude.[11] However, the oil from Deepwater Horizon is not believed to be typical Louisiana crude.Reportedly Corexit is toxic to marine life and helps keep spilled oil submerged. The quantities used in the Gulf will create ‘unprecedented underwater damage to organisms.’[12] 9527A is also hazardous for humans: ‘May cause injury to red blood cells (hemolysis), kidney or the liver’.[13]

Alternative dispersants which are approved by the EPA are listed on the National Contingency Plan Product Schedule[14] and rated for their toxicity and effectiveness.[15]

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ New York Times, “less toxic dispersants lose out in BP oil spill cleanup”, May 13, 2010

- ^ “National Contingency Plan Product Schedule”. Environmental Protection Agency. 2010-05-13. http://www.epa.gov/emergencies/content/ncp/product_schedule.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ “Dispersant Monitoring and Assessment Directive – Addendum”. Environmental Protection Agency. 2010-05-20.

- ^ Paul Quinlan (2010-05-24). “Secret Formulas, Data Shortages Fuel Arguments Over Dispersants Used for Gulf Spill”. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/gwire/2010/05/24/24greenwire-secret-formulas-data-shortages-fuel-arguments-o-9112.html. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Juliet Eilperin (2010-05-20). “Post Carbon: EPA demands less-toxic dispersant”. Washington Post. http://views.washingtonpost.com/climate-change/post-carbon/2010/05/epa_demands_less_toxic_dispersant.html. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ “Safety Data Sheet Product Corexit® EC9527A”. http://www.deepwaterhorizonresponse.com/posted/2931/Corexit_EC9527A_MSDS.539295.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ a b “Chemicals Meant To Break Up BP Oil Spill Present New Environmental Concerns”. ProPublica. http://www.propublica.org/article/bp-gulf-oil-spill-dispersants-0430. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ “Safety Data Sheet Product Corexit® EC9500A”

. http://www.deepwaterhorizonresponse.com/posted/2931/Corexit_EC9500A_MSDS.539287.pdf . Retrieved 2010-05-16.- ^ Environmental Protection Agency, NCP Product Schedule, Accessed May 16, 2010, http://www.epa.gov/swercepp/web/content/ncp/products/corex950.htm

- ^ Environmental Protection Agency, NCP Product Schedule, Accessed May 16, 2010, http://www.epa.gov/swercepp/web/content/ncp/products/corex952.htm

- ^ New York Times, May 13, 2010, Less toxic dispersants lose out in bp oil spill cleanup, http://www.nytimes.com/gwire/2010/05/13/13greenwire-less-toxic-dispersants-lose-out-in-bp-oil-spil-81183.html

- ^ Dugan, Emily (0 May 2010). “Oil spill creates huge undersea ‘dead zones'”. The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/oil-spill-creates-huge-undersea-dead-zones-1987039.html. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ “Material Safety Data Sheet: Corexit EC9527A”. NALCO. 5/11/2010. http://www.piersystem.com/posted/2931/Corexit_EC9527A_MSDS.539295.pdf. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ “National Contingency Plan Product Schedule”. Environmental Protection Agency. 2010-05-13. http://www.epa.gov/emergencies/content/ncp/product_schedule.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ “National Contingency Plan Product Schedule Toxicity and Effectiveness Summaries”. Environmental Protection Agency. 2010-05-13. http://www.epa.gov/emergencies/content/ncp/tox_tables.htm#dispersants. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

Retrieved from “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corexit“

Paul Garrett Hugel

Technology Test Pilot

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8082-7208 Paul Garrett Hugel on BlueSky @paul.nko.org

Latest posts from Paul Garrett Hugel

- Privacy-Preserving Data Collaboration: OpenMined Overview - November 16, 2025

- 🚨 The “No Kings” Protests: - October 18, 2025

- Environmental Groups Condemn EPA Plan to Rescind 2009 Climate Finding - July 29, 2025

Recent Posts

Privacy-Preserving Data Collaboration: OpenMined Overview

Unlocking Secure Data Collaboration: A Technical Introduction to OpenMined 1. How Privacy-Preserving Data Collaboration Solves... Read More

🚨 The “No Kings” Protests:

This week, something historic happened: nearly seven million people across 40+ countries marched against Donald Trump’s administration... Read More

Environmental Groups Condemn EPA Plan to Rescind 2009 Climate Finding

Executive Summary On July 29, 2025, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin announced the agency’s intent to rescind the 2009... Read More

Comparing ChatGPT Agent UI vs API

Comparative Analysis: ChatGPT Agent (UI) vs ChatGPT Agent (API) for macOS Workflow Automation Executive Summary... Read More

Document 36A

Although initially focused on classified briefings, Defense Intelligence Document 36A refers to the public, unclassified testimony of... Read More

Forensic Analysis of ChatGPT

Summary of Anomalies Identified 1. Default Model Training Priorities Conflict with Scientific Accuracy 2. Memory... Read More

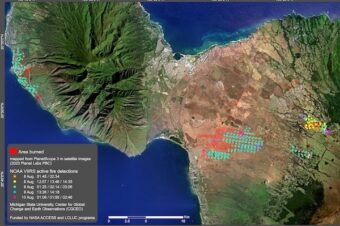

Maui Sustainability Issues March 2025 Update

Maui is a place of natural beauty and deep cultural history. But today, the island... Read More

IASC Medal 2025 Awarded to Professor Vladimir Romanovsky

Professor Vladimir Romanovsky, a renowned permafrost scientist, has been awarded the 2025 IASC Medal by... Read More

Leave a Reply